By Angela Gupta, reviewed by Matt Russell and Shirley Nordrum, UMN Extension Educators

Forests are vibrant changing ecosystems that are dynamic with plants, animals, fungi, weather and of course people. Minnesota’s woods are owned and managed (or not) by many thousands of private woodland owners and various local, county, state, federal and tribal agencies and organizations. Each land owner and land manager has their own hopes and dreams for the land. Commonly those goals include supporting healthy, sustainable and resilient forests; rarely is the goal explicitly to harvest timber. However, many landowners learn that harvesting wood is often an important part of cultivating healthy woodlands.

For many woodland owners, and maybe women especially, understanding how stewarding a healthy woodland can lead to a timber harvest includes a journey of learning, reflecting and incremental action. In an effort to start this journey, or offer insight for folks already on it, here are some ideas worth reflection.

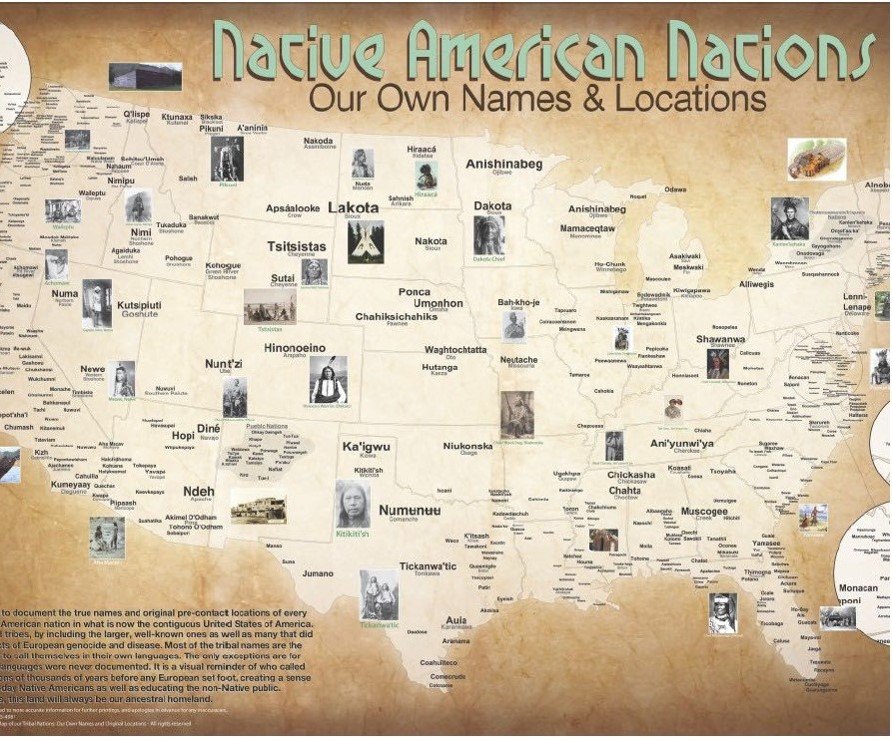

Minnesota’s woods have been inhabited by humans since the last glaciers receded. Humans settled the land that is now called Minnesota as the glaciers receded 12,000 to 10,500 years ago (MN Department of Administration Department of Archeology). Minnesota’s forests have always been managed for human food including meat, berries and nuts and used for medicine, shelter and transportation. Indiginous communities commonly used fire as a tool to manage plants and animals, moved seeds as they traveled between community sites, traded forest goods and used forest materials for transportation, shelter and cultural traditions (check out this new video: Oshkigin Spirit of Fire to learn more). The Dakota people’s origin story includes Bdote where the Dakota people and the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers joined about 10,000 years ago (learn more at the Bdote Memory Map). Never have Minnesota’s current forest types been “untouched by humans.” However the cultures, traditions and needs of the humans that use these forests have changed significantly along with the tools and goals of woodland managers.

Photos by Angela Gupta.

The last large-scale forest disturbance in Minnesota began with white settlement. Settlement accelerated after the United States Government’s Homestead Act of 1862, which empowered mostly white settlers to claim land previously used by indigenous tribes throughout the land that is today the United States. Settlers had to “file an application, improve the land, and file for deed of title.” Originally, to “improve the land” almost always meant cutting the forest to plant European-style agriculture fields or, for settlement under the the Timber Culture Act of 1873, planting and tending trees was required as proof of settlement. Rarely were the management of trees not part of the “improve the land” requirement for Minnesota settlers. The 1880s is also when the Great Lakes region, including Minnesota, dominated the timber industry's major forest cut (Wikipedia). In 1894, the Hinckley Fire burned over 300 square miles of cutover pine land - the logging debris was ripe to burn after a 2-month drought - resulting in about 418 human deaths (Massasoit Community College). For a time in the late 1890s Winona had more millionaires than any city of it’s size in the United States because of its strategic shipping position on the Mississippi and because of the amount of lumber that was coming out of Minnesota down the Mississippi River to timber markets elsewhere (Wikipedia). This period of Minnesota history drastically changed the forests and the humans that used them. Today’s forests are managed (or not) by humans and the forests are significantly younger and less diverse than the forests that existed before European settlement. These forests are also interspersed with European-style farms, towns and cities, mowed grass, domesticated livestock and pets and horticulturally designed yards. The land today looks very different from the spiritually significant, tended landscape stewarded for many millennia by the indigenous communities.

Today’s forests face additional unprecedented changes from climate change, invasive species and fragmentation. All of these changes are caused or exacerbated by humans today, and are happening more quickly than most other forest changes during the last 12,000 years. The world is grappling with climate change’s extreme weather. Increases in the frequency and intensity of floods, droughts, high winds and fires cause the most impact on Minnesota's forests. Wind storms and fires can cause drastic impacts to forests in only minutes. Furthermore, as Minnesota’s winters experience less extreme low temperatures, more species can survive in Minnesota than previously, including troublesome forest insects and diseases and invasive plants. More rain and increased overall temperatures also make Minnesota’s natural resources more habitable for many species. This coupled with fragmentation, often including settlements that intentionally plant and tend non-native plants (that all too frequently turn-out to be invasive), results in a forest that needs the loving stewardship of engaged land managers. A hands-off, “mother-nature-knows-best” approach is unlikely to have the intended healthy, sustainable and resilient outcomes most landowners want from their woods.

Removing trees and shrubs is an effective way to manage shade, nutrients, species composition and wildlife that use these dynamic ecosystems. Timber harvesting is often the most efficient way to meet landowner goals. There is an important difference between commercial timber harvesting, meaning someone is willing to buy the wood from the landowner, and non-commercial harvesting, meaning it’s not financially viable to sell the woody material. The difference is money: Does the landowner make money or spend money or resources? For most Minnosotan landowners today, these removals fall into one of two silvicultural categories: understory thinnings or overstory release harvests.

Understory removal is often a landowner’s introduction to active woodland management. Sadly invasive trees and bushes like buckthorn and honeysuckle are common in most natural areas in Minnesota. These understory species can cause major ecological damage in many ways. One recent study found that invasive shrubs stifle native species by decreasing forest floor temperatures (Penn State, Science Daily). Honeysuckle alone can reduce the basal area growth rate of a forest by 53%, meaning the trees are growing slower due to competition (Hartman & McCarthy, 2007). (Basal area is a complicated concept - it measures the cross sectional area of mature trees. A definatintion and schematic can be found on digital page 25 of this Woodland Stewardship book.) In a series of peer reviewed papers from McCarthy, et al, in 2004, 2007 and 2008, found that honeysuckle can reduce overall species diversity, negatively impact the seed bank and native tree and understory regeneration (Hartman & McCarthy, 2004, 2008). These invasive plants change the forest and the insects that live within these ecosystems. There’s clear data that invasive Japanese barberry increases tick populations, which may lead to increases in tick-borne disease in humans and that buckthorn is the overwintering host of the invasive soybean aphid (soybean aphid is a major pest for Minnesota’s soybean farmers, often requiring repeated insecticidal treatments on soybean fields). The good news is that active woodland stewardship can reduce negative impacts and create a healthier, more resilient and sustainable forest (UMaine News). Sadly understory removal, including invasive species management, is often expensive and time consuming, rarely merchantable, but a critical step in forest restoration and stewardship. (It’s worth noting that buckthorn has beautiful wood and is used by crafters including indigious groups.) Luckily, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources has a cost-share program to help woodland owners with projects like understory removals. Returning managed fires to the woods can also be a critical way to steward understory vegetation and woodland ecosystems.

Overstory release harvests can achieve resilient stand density and species diversity. This statement may also require a little gazing in the metaphorical rearview mirror. Prior to European settlement, bison and elk inhabited most of what is today the lower 48 states. Moose and woodland caribou also inhabited large sections of Minnesota. These large grazing animals ate understory plants and used forest edges. They were also critical food sources for most indigenous tribes, many of whom used fire to manage the vegetation and as a hunting tool. The combination of large herbivores and human land stewards resulted in a forest that was much more open and park-like then most of the forests we have today. In Charles Mann’s book 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, he dives deeply into the ecosystem and cultures that occupied this land for many millennia and enabled the first Europeans to ride long distances on horseback through forests without hitting their heads. Mann also writes about how human viruses brought by these first Europeans devastated native communities, which resulted in a significant reduction in land stewardship activity. This reduction in burning likely resulted in a major flush of young vegetation that may have contributed to the mini-ice age in Europe. Today most people are hard pressed to walk through the woods without getting hit in the face. Doing a release harvest can favor dominant, preferred trees or enable young trees to grow. These types of release cuts may be merchantable while also releasing sunlight, nutrients and altering the species composition to a more climate resilient stand that meets the landowner’s goals and improves habitat for select wildlife.

Photo by Angela Gupta.

Defining your landowner goals and understanding the silvicultural options is critical. Silviculture is the art and science of woodland management. Understanding what combination of woodland art and science is right for the existing and future forest are critical steps on the journey to a healthy, sustainable and resilient woodland. UMN Extension Forestry staff strongly encourage woodland owners to work with a forester or similar natural resource professional to get a woodland management plan before starting to manage their woods (a woodland management plan also makes many woodland owners eligible for an incentive program). There are many resources available to active woodland stewarders including boots on the ground engagement, and invasive species and forest regeneration incentive programs. One great, comprehensive resource to get you started is the book: Woodland Stewardship: A Practical Guide for Midwestern Landowners, 3rd Edition.

Much like the learning journey many woodland owners embark on during their tenure as land stewards, this short blog turned into a much longer essay. Thanks for reading to the end and I hope I’ve offered ideas for reflection and sparked motivation for active woodland stewardship. In another blog post I may reflect on the human benefits of working, breathing and reflecting in nature…

Additional resources:

Tangled Ecosystem: Soybean and buckthorn (7:21 video)

A book about making positive landscape changes one yard at a time: The Nature of Oaks: The Rich Ecology of Our Most Essential Native Trees by Douglas W. Tallamy